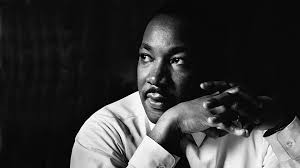

Born in 1929 to Alberta Williams and Martin Luther King Sr., Martin, as King Jr. was often called, was at the height of his notoriety as a national civil rights leader when he was gunned down by an assassin’s bullet in 1968. He was only 39 years old. He lived a very full life as a very young man.

King, Jr. was a father of 4, pastored his first congregation (Dexter Avenue Baptist Church) at 25, gave the world his I Have a Dream speech at 34, and received the Nobel Peace Prize at age 35.

King, Jr. was a father of 4, pastored his first congregation (Dexter Avenue Baptist Church) at 25, gave the world his I Have a Dream speech at 34, and received the Nobel Peace Prize at age 35.My first recollections of Dr. King came in the form of conversations I overheard my parents having in our home. Where he was and what he was doing had grown to be a constant topic of discussion. You see, Dr. King was my Uncle Samuel’s student and he would most often refer to him, in those formative years as, “that bright young man.”

My uncle was the Dean of Philosophy at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. I would hear my parents talk with him about the passionate discussions he enjoyed – debating the philosophies of Thoreau, Plato, Gandhi or some other great philosopher, with “that bright young man.” I recall the concern in their voices when the television blurted out the horrible news that the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama had been bombed. I recall, too, the sigh of relief my father had when he learned my uncle was not in the church that day and the pained look on his face as my uncle shared that four little girls had been killed.

My immediate family did not participate in the March on Washington, but our hearts were there. Uncle Sam’s bright young man was the leader of it. As one of the founding officers of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, my Uncle Sam was too. There was a tension in the house then as everyone was focused on and praying for the safety of the 250,000 marchers. So much could go wrong.

The remembrances of a 9-year-old girl are often sketchy, but nothing can wipe out the picture of those dogs and fire hoses being turned on the people of Birmingham, Alabama. The brutal attacks and humiliating antics openly perpetrated against student demonstrators hoping to win the right to sit and be served at a lunch counter are burned in my memory. The marches to win voting rights, the efforts to end job discrimination, the establishment of fair housing practices and the demolition of de facto segregation in the nation’s schools are all quite personal to me. They were my first lessons on civil rights, and there is nothing I can say that can adequately describe my feelings upon learning that those rights had so high a price.

A conversation held with my Uncle Sam just after Dr. King’s death provided me with a different perspective of this great man. According to my Uncle Sam, and easily substantiated in many essays Dr. King wrote, he was a reluctant leader. Dr. King, as his father and his father before him, wanted to be a good Southern Baptist minister. I’m sure you would agree he was just that. The knowledge gained in pursuit of his aspirations exposed Dr. King to the teachings of the world’s greatest minds. Sighting the words of many a great philosopher and adapting Gandhi’s non-violent strategies for social change, he was compelled to be the leader this nation’s fight for civil rights demanded. Rather than do what he wanted, what he found most personally expedient, became what a movement called him to be. His commitment to stand as a “Drum Major for Justice” positioned him in the seat of the master teacher.

Dr. King taught the world how to love. Sometimes it was tough love, as in the Montgomery bus boycott, the Sanitation workers strike in Memphis or the efforts to desegregate lunch counters at Woolworths in Alabama, but it was love, peace and justice he advocated nonetheless.

Dr. King was truly an instrument of peace. Celebrating his memory today is more than simply looking back on the accomplishments of a great man. Remembering his legacy, we are called to examine our own commitment to peace, love and justice. The question I most ask myself as I annually participate in Martin Luther King celebrations, when reading some excerpt from one of his essays or speeches, is: Linda, what have you done in the last year to keep King’s dream alive?

How many fingers would you need to answer the same question?

Linda M. Nance is President of the Annie Malone Historical Society and co-founded the Call to Conscience Readers Theatre Group. Linda is a published author, with articles in the St. Louis Post Dispatch, as well as the Missouri Historical Society’s quarterly publication. Her poems have been published in the Harvest Moon Anthology, and book reviews in the Sister’s Ninety Literary Journal. Linda also serves as an Oasis instructor.

Linda M. Nance is President of the Annie Malone Historical Society and co-founded the Call to Conscience Readers Theatre Group. Linda is a published author, with articles in the St. Louis Post Dispatch, as well as the Missouri Historical Society’s quarterly publication. Her poems have been published in the Harvest Moon Anthology, and book reviews in the Sister’s Ninety Literary Journal. Linda also serves as an Oasis instructor.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.